A Suicidal Murder

By Hy Conrad

Detective Bixby sighed and looked across to her son. “You like impossible crimes. Why don’t you take a look at this?”

Jonah and his mother were sitting across from each other at the kitchen table, both of them working on their homework for the evening. In Carol Bixby’s case, the homework was a homicide investigation.

“Sure.” Jonah liked any kind of crime, especially if it meant putting aside an English class assignment. “What kind of impossible crime?” He got up and walked around to look at the police reports spread out on the table.

“A murder made to look like suicide.” And she began to outline the case.

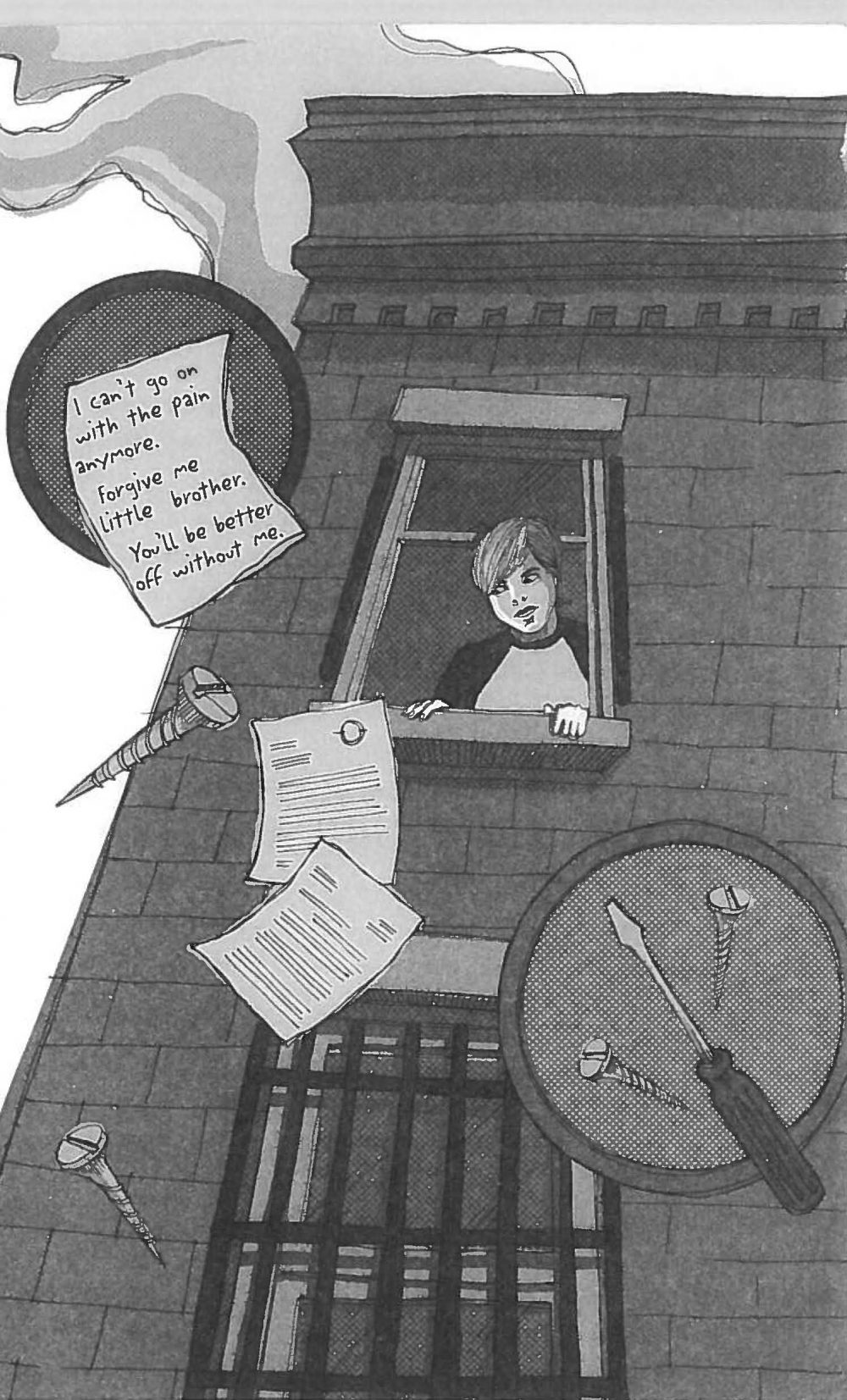

Simon Wentworth had been found on the street in front of the building where he lived. It seemed that the young man used a screwdriver to remove the child safety bars from a window in his high-rise apartment. Then he jumped to his death.

Among the photos was a picture of another window with the safety bars still attached to the outside of the building. “Looks like the bars would be tricky to remove,” Jonah observed.

“They’re supposed to be hard to remove,” said Carol. “Anyway, his prints were on the screwdriver and a suicide note was found in his room. No one else had been at home, according to the doorman. And his friends testified that he’d been moody and distracted lately. It’s got all the markings of a suicide. Except…” She sighed.

“We interviewed one his neighbors,” Carol continued. “Simon shouted, ‘No, no, no,’ before he jumped—and he screamed all the way down.”

“That doesn’t sound like suicide,” Jonah agreed,

Carol nodded. “It turns out Simon lived in the apartment with his older brother Teddy. We found a partial print of Teddy’s on the same screwdriver. So we had Simon’s suicide note analyzed by an expert and found a lot of similarities with Teddy’s handwriting. To cap it off, it seems the brothers had just taken out million-dollar insurance policies on each other’s life.”

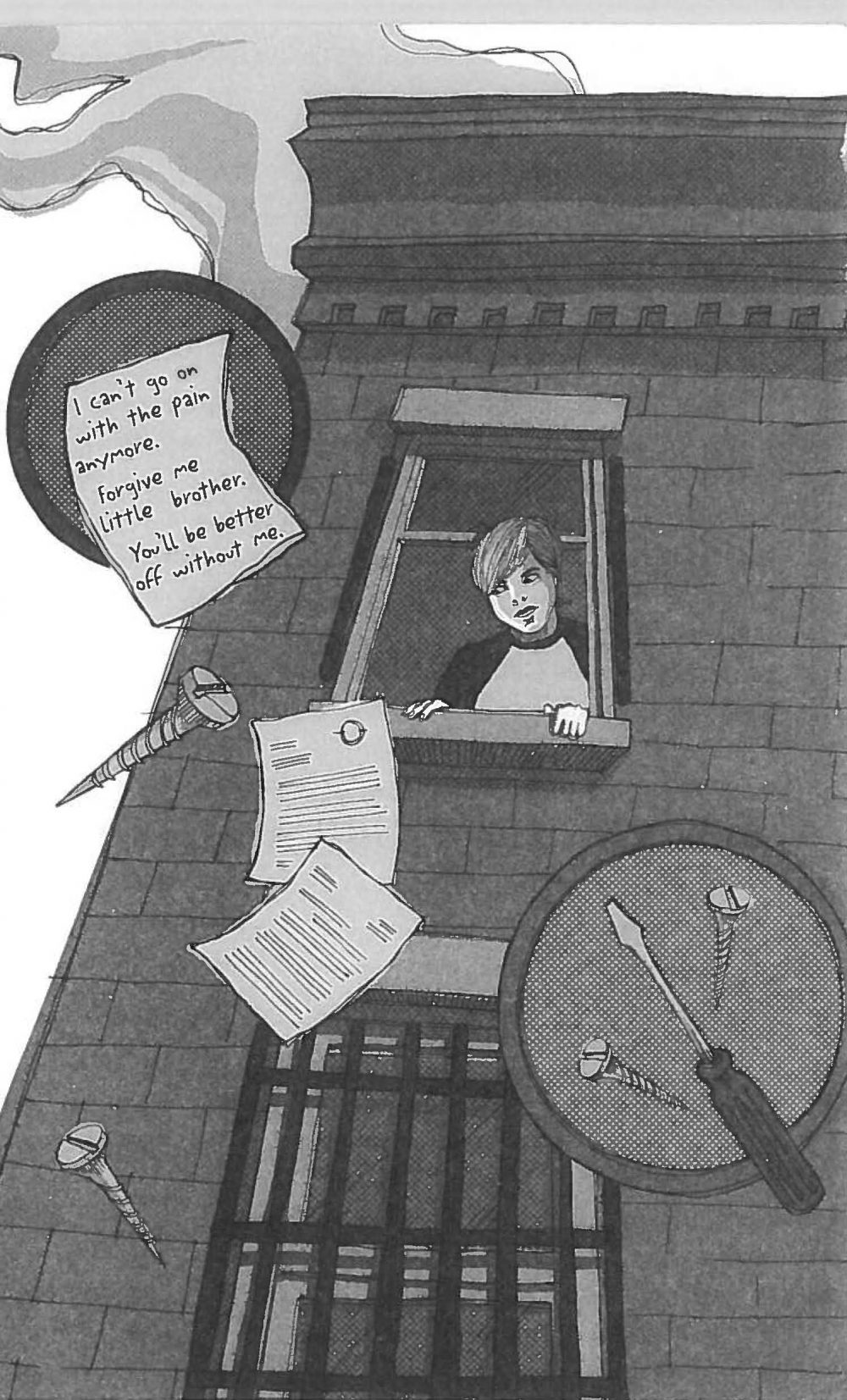

Jonah picked up a photocopy of the suicide note. It was short and sweet: “I can’t go on with the pain anymore. Forgive me, little brother. You’ll be better off without me.” He examined the penmanship and saw that it did look a little unnatural, with several fits and starts.

“What did Teddy say about his brother’s death?” Jonah asked.

“A cool customer,” said Carol, shaking her head. “He pretended to be distraught. He was the first to suggest that Simon’s death might be murder.”

“Let me guess,” Jonah said. “Teddy Wentworth has an alibi.”

“A great alibi. At the time Simon fell, Teddy was at his office, on the phone to a client in Los Angeles.”

“Maybe he was using a cell phone,” Jonah suggested.

“No,” said Carol, holding up a sheet of phone records. “He was on his land line at the office. And don’t forget the apartment doorman. He says Teddy didn’t come in or out the building all during that time.”

“Good puzzle,” said Jonah. He stood over the table full of papers and scanned them one by one.

“It’s not a puzzle,” Carol chided. “It’s serious. If we don’t figure this out, a killer is going to go free.”

“Well, I think I know what happened,” Jonah said slowly. “But you’re not going to like it.”

Jonah picked up the suicide note and pointed out two words. “It says ‘little brother’ here. But it should say “big brother.’ Teddy was older than Simon. Right?”

“Yes.” Carol studied the note again. “That’s weird.”

“Well, what if Teddy didn’t kill Simon? What if it was just the opposite? What if Simon was planning to kill Teddy? He writes a suicide note, trying to mimic Teddy’s handwriting. Then he leans out the window and unscrews the safety bars.

He’s getting ready for when Teddy comes home from work. But Simon loses his balance and falls. An accident. Simon is not only the victim—he’s also the killer.”

“What about the evidence?” Carol protested. “Teddy’s prints on the screwdriver?”

“A household screwdriver. Both of them used it. They both had million-dollar insurance policies. And if you’re planning to kill your brother, you’d probably be moody and distracted, too.”

“It makes sense,” Carol said reluctantly. I guess we were looking at the wrong brother.”